‘Social construct’ is a favourite bogeyman of the anti-PC brigade. These daring, freethinking spirits see dangerous relativism lurking behind this widely-accepted social science concept. The problem is that they generally do not understand what a social construct is. They are not alone: even many people dabbling on the more extreme side of ‘social justice’ seem to not fully grasp what it consists of. Social constructivism leads in fact to a rather pessimistic worldview, one with rather conservative expectations of change. Social constructs pinpoint really existing things, and structure and actors work together to keep them in place.

Blog

-

Indies Literature: Thoughts on ‘This Earth of Mankind’ by Pramoedya Ananta Toer

The Dutch lack of awareness of its colonial past has almost become a cliché. Anticolonial activists clamouring for compensiation and pundits nostalgic for a past where the Netherlands once dared to dream of a permanent seat on the UN Security Council both lament the uneducated state of the public. Their oft repeated complaint has actually much truth to it. Limited knowledge of the Netherlands East Indies is eclipsed by a general disinterest that seems to have set in as soon as the colonial army was disbanded.

Besides historians, only the sizeable part of the Dutch population with family ties to old Insulinde keeps its spirit alive. Besides the cuisine, and the annual pasar malam you will find in most cities, the flavours and fragrances of a world now gone have been preserved in the literature of the Netherlands. What is referred to as the Indische Letteren—or Indies Letters—is a well-curated part of Dutch literature looked after mostly by those who were originally born there.

However, this contains of course a coloured perspective, often drawing mostly from the experiences of a colonial upperclass that generally led privileged lives in their clean, well-staffed white villas. Attempts to portray the inlandse or native perspective are there—from the revolutionary Max Havelaar by Multatuli to the melancholic Oeroeg by the grande dame of the Indies Letters, Hella Haasse—but they remain colonial works.

After years of Dutch books, I therefore much enjoyed reading something from the Indonesian perspective. There is probably no better place to gain some understanding of the development of Indonesian nationalism than the literary masterpiece that is the Buru Quartet of Pramoedya Ananta Toer, who was until his dead perhaps Southeast Asia’s biggest chance for the Nobel prize. Born in 1925, this Indonesian nationalist suffered much in jail. He was first interred by the Dutch for anti-colonial sympathies, and later under Suharto for a much longer period because of suspected communist sympathies, and perhaps too much support for the Chinese-Indonesians.

In the labour camp on the rugged island of Buru where the military regime had put him, deliberately deprived of pen and paper, Toer wrote the first three of the four books in the tetralogy, composing orally. Fellow prisoners took on extra shifts to give him time, and saw to it that the voluminous tale was written down. They would finally be published in the eighties, then officially still banned in Indonesia itself.

I want to talk about the first book, because so far that is the only one I have read, in the Dutch translation, a few years back already. It is an incredibly interesting tale and I would recommend everyone interested in Indonesia’s modern history or literature to read it.

This Earth of Mankind (Bumi Manusia) to someone with an experience with the Indies Letters at first reads almost like another book from that genre, especially in the Dutch translation. The setting is familiar, the hierarchies and roles of the different races are all there. The main character is one of the rare none-whites admitted to the prestigious HBS-level secondary school, just like the eponymous main character of Haasse’s Oeroeg. The Dutch still have the absolute certainty of the correctness of their views and position that was typical of pre-Second World War Europeans. A mysterious Chinese baba runs the nearby brothel. The native rulers are as self-centred and inept as always.

However, soon you notice the stark difference in narrative style. The Indonesian landscape invites great literary descriptions. However, Toer provides a strong contrast with the Dutch writers. An example is Louis Couperus, the great naturalist. Most distinctly, in The Hidden Force (De Stille Kracht) he spends the first two pages beautifully setting the stage. However, like others, he shows something more akin to the admiration of something extraordinary and alien, the teeming forests and hazy hills contrasted against the empty flatness of the Dutch landscape.

This might be attributed to the fact that Toer’s work was composed orally. But it is also a sign of a more important difference: Toer has taken the Dutch narrative and turned it into something Indonesian. He takes it apart. When he sees the trees, he sees not the mysterious darkness, but the familiarity of his childhood. This Earth of Mankind breathes the idea that this part of the earth is home. It has in common with The Hidden Force that the land rejects the Dutch impositions, but for Couperus that turns it into something frightful rather than a source of power.

The first book of the four is not that martial yet. It describes only the first phase of nationalism, a gradual awaking by the main character and those around him to the unfairness of the colonial system. The main character, Minke, is a descendant of Javanese royalty, but in spite of his high status in indigenous society is despised by the arrogant Europeans. While in school he lives on a plantation in the household of an Indonesian woman and her daughter by an incompetent white Dutchman, Annelies. The women actually expertly run the plantation, but the mother’s knowledge and experience counts for nothing in the face of the colonial state. The main conflict arises when Minke marries the underage Annelies in a Islamic ceremony not recognised by Dutch law. Her legal, Dutch, guardians try to take her back and Minke rallies the Indonesians incensed by this insult to their religion.

This plot is in many ways the inverse of many conventional plots that focus on Dutch planters. The concubine and the appendages to heir household become the main focus, the white planter a supporting role. From inhospitable and mysterious, the kampongs become the place where family lives. The preoccupation with polite Dutch society is absent from Toer, which would make him less suitable for the costume period dramas so in vogue right now.

Most books from the Indies Letters let Islam play a role, but in most books it plays the role of a dark, unknowable power. For Toer it is not a negative force, but the source of the mobilising power that would eventually sweep away Dutch rule. Still, in the case of Islamic marriage law versus Dutch civil law I found myself instinctively agreeing with the Dutch court, or at least understanding of its position. It is hard to sympathise with the plight of a frustrated marriage to a minor. It is interesting how this case echoes Dutch fears about the violation of Maria Hertogh, the Dutch girl whose case caused race riots in Singapore in 1950. The Malay family that had adopted her while her white parents were locked away in Japanese concentration camps refused to give her up, and betrothed the underage girl to an older boy. Another echo is the important love story of Saïdjah and Adinda in Max Havelaar, which was also frustrated by Dutch colonial authorities.

Despite the different perspectives adopted by the Indonesian and the Dutch writers, I do see another parallel between This Earth of Mankind and Oeroeg, the tiny book from 1948 condemned by the representatives of a government fighting a war against the fledgling Republik Indonesia. In both, we have a ‘native’ boy gaining national consciousness as he learns to see the colonial system for what it is and understands Indonesia’s place in the world. This often painful process reminds me of the similar struggle I have read so much about that went on in China in the late 19th and early 20th century. It was this process that would determine the future shape of the postcolonial state. This is what makes This Earth of Mankind so rewarding to read: it is almost a meditation on nationalism. In the struggle for freedom of your community, it is one of the strongest weapons.

-

The laziness of Critical Theory

Critical approaches have done great work in social sciences, adding greatly to our collective insight. However, some scholars have taken the useful viewpoint it brings and turned it into a simplistic replacement of all other social science. For these critical theorists, mere deconstruction has replaced all other scholarship. The notion that all knowledge is premised on power has led the most publicly visible parts of Critical Theory down a path of taking apart all that came before without offering anything in return. However, we still live in this world and it does not go away just like that.

-

Before Europe Can Come Back, Does It Need A ‘Kniefall’?

For large numbers of peoples in the world, the decline of Europe meant their liberation. On his recent state visit in China, President Macron confidently stated ‘France is back. Europe is back.’ It is good for the European Union to stake out its own place in the world and develop an independent foreign policy. However, when we Europeans build this future, we have to grapple with the fact that, for many in the world, ‘imperial’ Europe does not refer to imagined ‘EUSSR’ horror scenarios the eurosceptics love to conjure up—but to imperial Europe, coloniser of much of the world.

The process of decolonisation is only a recent one, more recent than the horrors of the Second World War. Many African and Asian colonies only got their independence in the 1960s and 1970s. In East Asia, the Sultanate of Brunei became fully sovereign in 1984. Hong Kong lost its Crown Colony status as short ago as 1997. Liberation from European overlordship was often paid for dearly, with incredibly costly wars, both in terms of people killed and physical destruction. The Indonesian Revolution (1945–9), the Algerian War (1954–62), and the Portuguese Colonial War (1961–74) are only a selection. These bloody struggles were merely the closing episode to centuries of oppression, exploitation, and genocide. Europe—unlike settler colonies such as the United States—benefited from the physical remoteness of the violence in that it can keep it separate from its societies, but that ‘colourblindness’ has also desensitised it to the fact that for the formerly colonised the brutalities are all too salient still.

Before its neighbours would allow Germany to play a leading role again in Europe after the atrocities of the Second World War, the country had to follow a long path of atonement. Without the movement in the 1950s and 1960s that forced the Federal Republic to deal honestly with its past, Germany today would not only have been an entirely different country, but its eventual reunification would have been in question. The most powerful symbol of this atonement was the 1970 genuflection by Chancellor Willy Brandt (the Warschauer Kniefall) before the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. It mattered tremendously that the leader of West-Germany fell to his knees in the face of millions of death, not just because it symbolised accepting collective guilt, but maybe even more so the fact that it demonstrated a common European understanding of these past deeds as monstrous crimes.

Before its neighbours would allow Germany to play a leading role again in Europe after the atrocities of the Second World War, the country had to follow a long path of atonement. Without the movement in the 1950s and 1960s that forced the Federal Republic to deal honestly with its past, Germany today would not only have been an entirely different country, but its eventual reunification would have been in question. The most powerful symbol of this atonement was the 1970 genuflection by Chancellor Willy Brandt (the Warschauer Kniefall) before the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. It mattered tremendously that the leader of West-Germany fell to his knees in the face of millions of death, not just because it symbolised accepting collective guilt, but maybe even more so the fact that it demonstrated a common European understanding of these past deeds as monstrous crimes.The Holocaust and other nazi aggressions are unequivocally accepted as extreme crimes against humanity, by Germany and by its former victims. This fact reassures those countries, because this shared judgment means that a reformed Germany can be engaged without fearing that it will do the same again. (On a side note, this fact is also why the current Polish meddling with the common narrative is so potentially dangerous.) There does not exist, however, such a common agreement between Europe and its former victims on its past crimes.

During the campaign for the 2017 French presidential elections that ended with him in the Palais de l’Élysée, Emmanuel Macron was ferociously attacked by the centre-right contender after Macron had admitted France that had committed crimes against humanity in Algeria. Opponent François Fillon claimed that France should not be blamed for ‘partager sa culture’, sharing its culture. UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson saw no issue with reciting imperial poet Rudyard Kipling while on an official tour of a Buddhist temple in Myanmar, and has in the past suggested the recolonisation of Africa. There is no universal agreement in Europe about the fact that in scale of destruction and intensity of violence colonialism in a certain view went far beyond what the Holocaust has done to Europe. There is certainly not a shared narrative with its former victims.

In a speech on the Dutch history in what since 1945 is Indonesia, the Dutch Prime Minister stressed the need for a common history before one can move forward. A similar motive underlies flagging attempts to write an ‘East Asian’ history textbook with Chinese, Japanese, and South Korea involvement. However, passively waiting for such agreement to spontaneously arise will not do. The Warschauer Kniefall is an example of how grand gestures can contribute to a closer understanding. Perhaps former European colonisers should start considering symbolic ways to move towards recognition of the perspective of the colonised. Until then, these countries should not be surprised if the West’s Rest is not jumping for joy at the thought of a European revival.

Europe can proudly proclaim to be back on the world stage, but currently it would do so unaware that to others this would sooner bring back nightmares than cause jubilation.

-

Avoiding Yellow Peril amid PRC infiltration

With legislation introduced in Australia’s parliament which Prime Minister Turnbull has explicitly said is meant to counter Chinese interference, the efforts of Beijing to shape the world have been brought to the fore like they haven’t in quite some time. Across the Western world, governments and companies are realising that behind Chinese acquisitions and investment might be a conscious influence-building agenda that transcends economic rationale. The accusations that the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) depends on projects that are economically not viable seem less important now. Sri Lanka’s inability to pay back loans led to it handing control over the Chinese-built Hambantota port to Beijing. The power China has over Venezuela and Zimbabwe has been in the press as well.

However, the creeping global influence of the regime in Beijing should not lead us in the West to condemn ‘the Chinese’ en bloc. The West has a long history of ‘Yellow Peril’ narratives and while addressing the very serious issue of Communist Party of China (CPC) abusing the openness of Western countries we should take care to distinguish between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and ‘the Chinese’. Already, reports by Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) about the danger of Chinese infiltration has led to some unease in the Chinese community in Australia. Not all ethnic Chinese are a threat. Reporting should take care to reflect this.

This might be even more necessary because often the first target of PRC overseas operations are overseas Chinese communities. Every PRC embassy has an officer for Overseas Chinese Affairs (华侨事务 huáqiáo shìwù, shortened to 侨务 qiáowù) who concerns themself with bringing the local Chinese community in line with the CPC. This includes ensuring joyful flag-wavers whenever Chairman Xi Jinping or another Chinese leader makes a foreign visit, but also organising angry nationalists to, for example, shout over pro-Tibet demonstrations and allegedly to beat up demonstrators. It moreover includes overseeing Chinese Scholar and Student Associations (CSSAs) that keep tabs on Chinese students and impel them to inform on each other. Often, the poorer students are encouraged with financial rewards to do so. Lastly, it tries to keep the local business community in line.

Chinese embassies have this power because of the enormous economic importance of China, especially to Chinese business communities that distinguish themselves based on their ties to the PRC. Perhaps it were these business interests that made ethnic Chinese businessmen in Kuala Lumpur in 2015 happy to welcome the PRC ambassador to tour Petaling Street after Malay riots. Recently, the Chinese ambassador even accompanied an MP of opposition party DAP on house visits. Ambassador Huang’s remarks about anti-Chinese racism and separate remarks declaring the safety of ethnic Chinese a national interests of the PRC only fuel racists in UMNO who still see the ethnic Chinese as foreigners under foreign tutelage.

The year 2016 saw the PRC’s claim of ownership over ethnic Chinese wherever they live in the world also hit Singapore. Various issues—including the remaining military links of the Republic with Taiwan and its pro-international law stance in the South China Sea—had been grating Beijing for a while, and it was probably this older unhappiness that caused such an outburst that year. Talking to people at Peking University, I got the impression that the root of this cause is the supposed ‘Westernisation’ of the Singaporeans, who are losing their Chineseness—no matter that the ancestors of ~25% never had any ‘Chineseness’ to begin with. When Lee Kuan Yew passed away in March 2015, on the Chinese internet several nationalists saw it fit to call him a 汉奸 (hànjiān), traitor of the Chinese race, for selling out ‘his’ Chinese to the West.

Increasingly, as the CPC turns to traditional culture as its source of legitimacy, Beijing has to present itself as the guardian of Chinese civilisation. In a speech to overseas Chinese I have looked at earlier, Chairman Xi Jinping implied that their Chinese heritage ought to lead ethnic Chinese to staunchly support the ‘motherland’ and with that of course the Party. In Chinatowns across the world, Chinese businessmen with links to the PRC take over papers and Chinese schools. A granny who has read her local Chinese-language news for decades suddenly finds her trusty source of news following the Party line, no matter that she herself might actually have fled from that Party. Chinese community organisations abroad are reminded by the local qiáowù official where their business interests lie and need not much further instruction.

The danger of ‘infiltration’ is then much more serious and much further along already for ethnic Chinese communities across the world. This has real-life consequences, especially when ethnic Chinese find themselves in PRC (or Hong Kong) jurisdiction. Australian

citizenpermanent resident, professor Feng Chongyi, discovered this as he was barred from leaving the PRC, but we can also see this in much more severe punishment for ethnic Chinese businessmen who find themselves in trouble with the law as compared to other businesspeople with foreign nationalities.That we have to deal with this issue is clear. As the CPC refines its methods, we will see more stories like the current Australian saga pop up. However, it is essential that we do not chalk this off to interference by ‘the Chinese’. It is true that Beijing seeks to mobilise overseas Chinese communities—in the case of Australia the PRC embassy in Canberra shockingly threatened the government to instruct the Chinese community to vote against the Australian Labor Party—but by talking about the Chinese as one monolith we only give the PRC the ownership it wants. What we need to do is recognise the experiences of ethnic Chinese around the world, since they have battled with this issue for much longer.

The Century of National Humiliation narrative that shapes Chinese nationalism bemoans the loss of Chinese dominance. This is said to have not only lead to the lamentable loss of geographical bodies, but also to the humiliating loss of human bodies. Rejuvenation or restoration (复兴 fùxīng), the core of Chinese ambition, would in the eyes of nationalists include restoration of Chinese control over ‘Chinese’ bodies. Other countries thus have to spend more attention to protect those among their citizens who happen to be of ethnic Chinese descent. This requires distinction between the country and the civilisation.

-

Never Forget Chinese Nationalism’s Ethnocentrism

Saying that Chinese increasingly assertive nationalism has a rather ethnocentric streak is nothing new, at least not for those who follow China. However, only when you actually read the source material in Chinese, is the starkness of the PRC’s racialism really driven home. This is something analysts, and other people paid to have opinions on China, should do more often, especially when the English translation often softens the edges a bit.

To demonstrate this, I will quote a paragraph from Mark Zuckerberg’s favourite Xi Jinping book—The Governance of China. This collection of formulaic speeches—complete with hagiographic pictures of Chairman Xi doing important things—contains a speech he gave on 6 June 2014 to the Seventh Conference of the Friendship of Overseas Chinese Associations (世界华侨华人社团联谊) entitled ‘The Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation Is a Dream Shared by All Chinese’. The title already confronts us with translation issues: In the Mandarin name of the association, ‘Overseas Chinese’ is written as ‘华侨华人’, which introduces is to the difficulty of the English word ‘Chinese’.

-

On studying in China

Later this afternoon I leave for the People’s Republic to start my first of two semesters at Peking University, close to Beijing’s beautiful Summer Palace in the northwest. While I like to kid that I look forward most of all to the food, I will also enjoy the opportunity to study and learn about China. But coming to China from Europe, where you cannot help but be exposed to all sorts of stereotypes, assumptions, and truisms, it might be healthy to reflect a bit on how exactly I will study there before I leave.

-

Carving up the Girdle of Emerald: colonialism’s violent cleavages

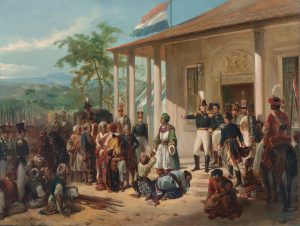

The 1830 painting ‘The Submission of Prince Dipo Negoro to General De Kock’ by Nicolaas Pieneman is a good example of Dutch portrayals of the Indies. The evil of colonialism is not expressed in a sum of its benefits and downsides. These debates over British railways in India and economic development miss the point of colonialism entirely. Colonialism is violence. It is not just that it entails violence as an inevitable product of its system, colonialism itself is an act of epistemic violence. Colonies require colonial subjects, which needs a cleavage to separate the humans from the lesser creatures.

In my Dutch primary school our teacher would illustrate history class with the school’s antique school prints. They piqued my interest in East Asia, but in hindsight they were rather orientalist. Invariably, you would see a pittoresque landscape, a mise-en-scène of stern Dutch overlooking interchangeable inlanders going about their daily business, or unwavering Dutch ships of the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC). For a little bookish boy longing for a more exciting world these heroic tales of ‘discovery’ were enthralling.

Our classes put less emphasis on the unfortunate collateral damage of these exciting adventures. The prints perpetuated the unaddressed colonial gaze, as the teacher left out the fundamentals of the story: the dependency of colonialism on violence. First, metal violence, in the mind of the colonist. After that, physical. Then, after armed resistance has been eliminated and the people’s bodies are subjugated, the work of mental domination begins. The tools: dichotomies. A community is taken and carved up into slices. Those slices are carved up again: superior versus inferior, salvageable versus beyond civilisation, useful versus useless, rational versus irrational, etc.

-

Is China trying use the COC to beef up its Article 281 defence?

Besides ‘we do not accept,’ another legal argument China used to argue that the Philippines case before An Arbitral Tribunal under Annex VII of UNCLOS was inadmissible was that the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC) in the South China Sea prevented arbitration as per UNCLOS Article 281. This article states that if states have agreed on a way to settle the dispute, no case can be brought in that area. However, the tribunal quashed the reasoning that the DOC prevents it from judging in this case in its award on admissibility of 29 October 2015.

Following the frenzy after the tribunal released its final decision on 12 July 2016, there have been various attempts to lower the tensions. Both sides appear committed to keep the peace, even if reaching an agreement proves difficult. At the same time, however, states are positioning themselves for future possible legal challenges. Some claimant states may see the Philippines’ success as encouragement to start their own cases. China must be preparing for such eventuality already by beefing up its legal defences. One area I think we should keep an eye on is Article 281.