Xi Jinping’s well-documented attempts to become ‘chairman of everything’—as several observers have argued before me—are in fact a testament to his need to shore up weak central power. The Chinese party-state works through broad project campaigns, launched through the apparatus of party committees and propaganda organs. Local leaders take the cue to come up with actual policies, of which the centre then picks a few to serve as example. This works under leninism-enforced ideological unity. However, the fundamental shift in Chinese society since the Opening and Reform period has cast the ship of party-state on unruly seas. Local authorities’s power and responsibilities have grown while discipline of thought has slackened. In response to this uncertainty the leadership’s party reflexes have brought about the authoritarian turn of the past decade. The old story of Mao’s revolution discredited, the Chinese Communist Party’s hold over is now first of all material. The Party needs a new legitimising tale to mobilise its people. It better be convincing. So now it attempts to equalise the Party with the State with the Nation with the People. But by turning to traditional nationalism, the formerly revolutionary replace a self-written story with an older narrative that does not necessarily require the Party.

These narratives matter. People make sense of the world through stories they tell themselves. These stories have their own internal logic, a plot that explains how we got here and points to the future. We cast the people and groups we encounter as characters in this story, allowing us to quickly make sense of everyone’s (and everything’s) place and extrapolate from there. The Cold War was such a powerful frame, because it was a good story. For the people on both sides the two camps of good and evil made it easier to place countries and individuals, and decide how to behave towards them.

Xi Jinping’s tenure has sped up the post-1989 nationalist turn in Chinese politics. The CCP’s shift in legitimising narrative—away from communist revolution of the workers of the world, to a nationalist rejuvenation of the Chinese ethno-nation—means that the dictatorship of the proletariat, i.e. continued rule by a leninist vanguard party, is not longer absolutely essential to the official goal. Instead, the main actor has now become the Chinese Nation, an old and familiar character. The new story is the Chinese Dream, which in full is the ‘Chinese Dream of the Grand Rejuvenation of the Chinese (Ethno-)Nation’ (中华民族伟大复兴的中国梦 zhōnghuá mínzú wěidà fùxīng de zhōngguó mèng).

To an orthodox marxist-leninist communist narrative the revolutionary party is fundamental. The vanguard has supposedly achieved awareness of the laws of history, and use their understanding to lead the proletariat to victory. Party cadres and other government officials in China still learn the theories of marxism-leninism-maoism in the party schools they have to regularly attend for training and retraining. This socialises them in party thought: the goal is for them to learn there is how to think, speak, and write in terms of the latest ideological orthodoxy. However, even for the average bureaucrat, the future of China is less about achieving communist utopia than it is about national revival, albeit phrased in terms of historical materialism. It seems less obvious that the continued existence of communist party rule in China is an essential requirement of the nationalist narrative of the Great Rejuvenation.

This does not mean that the CCP has been weakened already. Short-term, nationalism probably boosts the Party’s popular support. Leninist systems provide immensely powerful organisational tools that few Chinese nationalists would discard lightly. After all, the defeated Nationalist Party, the Kuomintang, attempted to use the same organisational model. However, this strategic legitimising shift has knocked out a few key supporting beams in the narrative structure. For an orthodox bolshevik revolution, one absolutely needs a vanguard party. Its continued monopoly of power is required for the eventual transition to communism. The marxist-leninist one-party state is at the centre of this well-worn plot. But national revivals can take many forms. Already, mainland New Confucians are reviving talk about ‘national religion’ and reintroducing the old Chinese-barbarian distinction. Far right commentators seem to care little beyond whatever can provide national power. If, amid escalating censorship, it has not become much easier to talk about a China without the Party in official discourse, it has at least become possible.

When the era of high maoism came to its end, the CCP under Deng Xiaoping began updating the Party’s ideological justification: the need to sacrifice consumer welfare for the eventual achievement of communism was replaced with economic growth in the now. After the brutal crackdown on the June 4 movement in 1989 that famously centred around the Tiananmen Square protests, the Party’s ability to achieve nationalist goals and material benefits became the key to make people forget about politics. Even then Deng maintained that the eventual goal of communism was still the Party’s target. But—as with any millenarian faith forced to deal with the failure of the end-time to arrive within the promised timespan—the leader now held that this was still generations away. Still, the goal was maintained, if only formally. Xi Jinping, descendent of a revolutionary hero and allegedly a true believer in the Party, has given this idea a new lease of life. Last April, Qiushi, the theory journal of the CCP, republished an expanded version of a 2013 speech by him that stressed that China is still a socialist country and that it still aims to (eventually) achieve ‘the lofty ideals of communism and the common ideals of socialism with Chinese characteristics’.

This reverses a decline in the importance given to the revolutionary narrative of the CCP’s right to rule. Under Xi Jinping the CCP is pursuing ideology at the cost of economic growth. Party control and the dominance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) goes above trade and private companies. The flexibility offered by sleights of hand such as ‘XX with Chinese characteristics’ and updating the ‘primary contradiction’ does reduce the distance between ideology and reality that Václav Havel identified as post-totalitarianism’s weakness. But the communist ideology still might only appeal to the Party bubble.

Deng Xiaoping limited his Reform to what was required for economic growth, leaving the constitutional system and the elite layer largely intact. For the average Chinese the period of Opening and Reform was a massive change. But the party nomenklatura still live their separate lives in the system. Party schools, cadre housing, preferential health care, and for some even a separate food supply mean that they live in a different world, even into retirement. Privileged cadres read internal newspapers and socialise with their own. In the past, the whole of society was integrated into the communist system through the hierarchy of work units. Now, most people no longer follow the same logic. Even the recently arrested marxist students do not subscribe to the CCP’s official ideology, but act outside the Party.

The leadership is in fact aware of the problem. The Politburo stresses the critical need to improve effectiveness of political education in schools for a reason. Propaganda campaigns strive to bring home the orthodoxy all the way to your apartment’s lift. But for most—for as far as they pay attention—the main take-away from this onslaught consists of the two remaining sources of party legitimacy: economic well-being and Chinese nationalism. The improvement in Chinese living standards has been so substantial and is so recent that the Party’s claim to the credit would probably survive a recession. Moreover, the political system allows control over the fiscal and monetary levers, as well as the statistics. The Belt and Road Initiative, backed by state policy banks, guarantees that the debt-fuelled model of growth through infrastructure will go on for a while, just as China’s work on building higher-level domestic manufacturing are showing results. The narrative is clear: China’s growth was made possible through the Opening and Reform policies, an achievement of the Chinese Communist Party. The risk is not that this narrative turns against the Party, but that it fades away as the middle classes become accustomed to regarding their middling wealth as the norm.

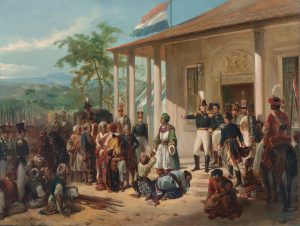

The problem is the nationalist narrative. The Chinese Communist Party propaganda and the ‘patriotic education’ that began in the schools in 1990s base themselves on an old narrative: the idea of cleansing the shame of the ‘Century of National Humiliation’ (百年国耻 bǎinián guóchǐ). The Century refers to the period of Western and Japanese despoliation of the country, roughly starting with the First Opium War in 1839 and ending after the Second World War. This is a powerful story, but not one that was written by any particular party.

Work by William Callahan traces the first National Humiliation Day to 1915. In late May the National Teachers’ Association picked 9 May to commemorate the shame of the Japanese imperialist Twenty-One Demands that were put to the government on that date. The May Fourth movement of 1919— the centennial of which just passed—called for wholesale modernisation to end the nightmare of impotence. When the Kuomintang got hold of the Republic of China in 1927–8 it made National Humiliation Day a national holiday. Just as the Chinese Civil War picked up again, it declared the national shame ‘cleansed’ by its efforts: the Western powers had given up their extraterritorial rights in 1943 and Japan was defeated in 1945. Soon they would be swept aside in a ‘humiliation’ their propaganda blamed on the imperialist Soviets. In their turn, the communists claimed to have cleansed the nation’s shame with their victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949, when Mao Zedong proclaimed from the rostrum of the Forbidden City that China had finally ‘stood up’.

But after 1989 the narrative made a comeback with the nationalist turn in propaganda. National Defence Education Day is now a public holiday. Cleansing the shame of national humiliation is linked explicitly to the Chinese Dream of the Grand Rejuvenation of the Chinese Ethno-Nation that the Party is supposed to bring about. The end of British colonial rule in Hong Kong was a major cause for celebration. Controlling the South China Sea, achieving great power, and ‘returning’ Taiwan status are all markers of this revival.

But the Party should be careful what it awakens. The narrative of national humiliation has roots in late-19th century nationalism. Its main concern was to, before anything, create a Chinese nation, and then find a means to defend it. It did not matter what means. In fact, this utilitarian approach is what brought many Chinese intellectuals to communism in the first place: without having read much marxism they put their hopes on bolshevism to salvage ‘China’ after the October Revolution in Russia had proven its power. The history of China until 1949 is one of ministers and governments who were seen as weak and unable to stop the humiliation becoming the target of irate nationalists one by one. Some of the most successful CCP propaganda in the 1930s and 1940s was based on accusing Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist Party of selling out to the Japanese and Western imperialists. Chiang, in turn, accused the CCP of being a pawn of the equally foreign Soviets.

The main point is that the logic of the story has changed. The old nationalist narrative, now revived by the Party, has a different plot: rather than a revolutionary narrative of making China communist, this story is about saving the Chinese nation. The quest it has always contained within itself is to find a method that can finally achieve this. The CCP still has good grounds to argue that it has found the solution. But in reality history does not progress in simple linear fashion. The narrative now no longer absolutely requires a revolutionary vanguard party to safeguard the dictatorship of the proletariat. The dictatorship of the proletariat is now merely a means to be judged on its efficacy. When some unforeseen setback to the nationalist project makes it appear that the CCP is but a necessary evil or even a hindrance, inconsistencies will begin to pop up. A narrative can persist with such contradictions for a long time, but a crisis can force a reevaluation of the ‘logical’ conclusion of the plot. Thus weakened, the building of legitimation may prove to be unable to withstand next time a storm comes about.

If Beijing notices that this starts to happen, it will have to devise ways to make sure people do not think for themselves too much. This is why Xi Jinping is so obsessed over ideological control. The more the lower ranks lose faith in communism, the more he needs to centralise power to the core holdout of remaining faithfuls. But such moves weaken the effectiveness of the leninist organisation model. Leninist parties operate in a modular fashion with a great deal of de facto decentralisation. This is possible because its people have been moulded into its ideology and submit to the party, which they see the indispensable means to a shared (often millenarian) goal. When that is no longer the case, its authoritarian instincts will induce the party elite to pursue a project of centralisation that unavoidable reduces government effectiveness.

Of course, one solution to this problem would be for the CCP to come up with a new, coherent narrative of which it is an integral part and force it on the whole of society into it. After all, in Singapore, the ‘leninist-inspired’ PAP still manages to sell itself as indispensable, despite the absence of a revolutionary narrative. However, achieving this is exceedingly difficult, especially in a country much larger and much more diverse. The rhetoric of Chinese socialism is still the only way party cadres are taught to think about politics, even as nationalism dominates the propaganda outside the Party. Just as a growing part of the Singaporean population feels increasingly detached from its leaders’ policy-speak, so do many Chinese simply brush off Xi Jinping’s New Thought. Cynical compliance because of material inducement is a paltry replacement for true faith in the Cause. A switch to a properly neo-fascist nationalism would probably require a war of aggression. A radically new narrative often needs a Big Event to gain hold. But not only would that have dire consequences for China’s neighbours, the current creeping inconsistency in the narrative also means it could have unexpected consequences for he who is for now still safely ensconced in the Forbidden City as the Chairman of Everything.