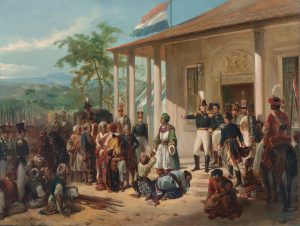

The Dutch lack of awareness of its colonial past has almost become a cliché. Anticolonial activists clamouring for compensiation and pundits nostalgic for a past where the Netherlands once dared to dream of a permanent seat on the UN Security Council both lament the uneducated state of the public. Their oft repeated complaint has actually much truth to it. Limited knowledge of the Netherlands East Indies is eclipsed by a general disinterest that seems to have set in as soon as the colonial army was disbanded.

Besides historians, only the sizeable part of the Dutch population with family ties to old Insulinde keeps its spirit alive. Besides the cuisine, and the annual pasar malam you will find in most cities, the flavours and fragrances of a world now gone have been preserved in the literature of the Netherlands. What is referred to as the Indische Letteren—or Indies Letters—is a well-curated part of Dutch literature looked after mostly by those who were originally born there.

However, this contains of course a coloured perspective, often drawing mostly from the experiences of a colonial upperclass that generally led privileged lives in their clean, well-staffed white villas. Attempts to portray the inlandse or native perspective are there—from the revolutionary Max Havelaar by Multatuli to the melancholic Oeroeg by the grande dame of the Indies Letters, Hella Haasse—but they remain colonial works.

After years of Dutch books, I therefore much enjoyed reading something from the Indonesian perspective. There is probably no better place to gain some understanding of the development of Indonesian nationalism than the literary masterpiece that is the Buru Quartet of Pramoedya Ananta Toer, who was until his dead perhaps Southeast Asia’s biggest chance for the Nobel prize. Born in 1925, this Indonesian nationalist suffered much in jail. He was first interred by the Dutch for anti-colonial sympathies, and later under Suharto for a much longer period because of suspected communist sympathies, and perhaps too much support for the Chinese-Indonesians.

In the labour camp on the rugged island of Buru where the military regime had put him, deliberately deprived of pen and paper, Toer wrote the first three of the four books in the tetralogy, composing orally. Fellow prisoners took on extra shifts to give him time, and saw to it that the voluminous tale was written down. They would finally be published in the eighties, then officially still banned in Indonesia itself.

I want to talk about the first book, because so far that is the only one I have read, in the Dutch translation, a few years back already. It is an incredibly interesting tale and I would recommend everyone interested in Indonesia’s modern history or literature to read it.

This Earth of Mankind (Bumi Manusia) to someone with an experience with the Indies Letters at first reads almost like another book from that genre, especially in the Dutch translation. The setting is familiar, the hierarchies and roles of the different races are all there. The main character is one of the rare none-whites admitted to the prestigious HBS-level secondary school, just like the eponymous main character of Haasse’s Oeroeg. The Dutch still have the absolute certainty of the correctness of their views and position that was typical of pre-Second World War Europeans. A mysterious Chinese baba runs the nearby brothel. The native rulers are as self-centred and inept as always.

However, soon you notice the stark difference in narrative style. The Indonesian landscape invites great literary descriptions. However, Toer provides a strong contrast with the Dutch writers. An example is Louis Couperus, the great naturalist. Most distinctly, in The Hidden Force (De Stille Kracht) he spends the first two pages beautifully setting the stage. However, like others, he shows something more akin to the admiration of something extraordinary and alien, the teeming forests and hazy hills contrasted against the empty flatness of the Dutch landscape.

This might be attributed to the fact that Toer’s work was composed orally. But it is also a sign of a more important difference: Toer has taken the Dutch narrative and turned it into something Indonesian. He takes it apart. When he sees the trees, he sees not the mysterious darkness, but the familiarity of his childhood. This Earth of Mankind breathes the idea that this part of the earth is home. It has in common with The Hidden Force that the land rejects the Dutch impositions, but for Couperus that turns it into something frightful rather than a source of power.

The first book of the four is not that martial yet. It describes only the first phase of nationalism, a gradual awaking by the main character and those around him to the unfairness of the colonial system. The main character, Minke, is a descendant of Javanese royalty, but in spite of his high status in indigenous society is despised by the arrogant Europeans. While in school he lives on a plantation in the household of an Indonesian woman and her daughter by an incompetent white Dutchman, Annelies. The women actually expertly run the plantation, but the mother’s knowledge and experience counts for nothing in the face of the colonial state. The main conflict arises when Minke marries the underage Annelies in a Islamic ceremony not recognised by Dutch law. Her legal, Dutch, guardians try to take her back and Minke rallies the Indonesians incensed by this insult to their religion.

This plot is in many ways the inverse of many conventional plots that focus on Dutch planters. The concubine and the appendages to heir household become the main focus, the white planter a supporting role. From inhospitable and mysterious, the kampongs become the place where family lives. The preoccupation with polite Dutch society is absent from Toer, which would make him less suitable for the costume period dramas so in vogue right now.

Most books from the Indies Letters let Islam play a role, but in most books it plays the role of a dark, unknowable power. For Toer it is not a negative force, but the source of the mobilising power that would eventually sweep away Dutch rule. Still, in the case of Islamic marriage law versus Dutch civil law I found myself instinctively agreeing with the Dutch court, or at least understanding of its position. It is hard to sympathise with the plight of a frustrated marriage to a minor. It is interesting how this case echoes Dutch fears about the violation of Maria Hertogh, the Dutch girl whose case caused race riots in Singapore in 1950. The Malay family that had adopted her while her white parents were locked away in Japanese concentration camps refused to give her up, and betrothed the underage girl to an older boy. Another echo is the important love story of Saïdjah and Adinda in Max Havelaar, which was also frustrated by Dutch colonial authorities.

Despite the different perspectives adopted by the Indonesian and the Dutch writers, I do see another parallel between This Earth of Mankind and Oeroeg, the tiny book from 1948 condemned by the representatives of a government fighting a war against the fledgling Republik Indonesia. In both, we have a ‘native’ boy gaining national consciousness as he learns to see the colonial system for what it is and understands Indonesia’s place in the world. This often painful process reminds me of the similar struggle I have read so much about that went on in China in the late 19th and early 20th century. It was this process that would determine the future shape of the postcolonial state. This is what makes This Earth of Mankind so rewarding to read: it is almost a meditation on nationalism. In the struggle for freedom of your community, it is one of the strongest weapons.

Before its neighbours would allow Germany to play a leading role again in Europe after the atrocities of the Second World War, the country had to follow a long path of atonement. Without the movement in the 1950s and 1960s that forced the Federal Republic to deal honestly with its past, Germany today would not only have been an entirely different country, but its eventual reunification would have been in question. The most powerful symbol of this atonement was the 1970 genuflection by Chancellor Willy Brandt (the Warschauer Kniefall) before the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. It mattered tremendously that the leader of West-Germany fell to his knees in the face of millions of death, not just because it symbolised accepting collective guilt, but maybe even more so the fact that it demonstrated a common European understanding of these past deeds as monstrous crimes.

Before its neighbours would allow Germany to play a leading role again in Europe after the atrocities of the Second World War, the country had to follow a long path of atonement. Without the movement in the 1950s and 1960s that forced the Federal Republic to deal honestly with its past, Germany today would not only have been an entirely different country, but its eventual reunification would have been in question. The most powerful symbol of this atonement was the 1970 genuflection by Chancellor Willy Brandt (the Warschauer Kniefall) before the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. It mattered tremendously that the leader of West-Germany fell to his knees in the face of millions of death, not just because it symbolised accepting collective guilt, but maybe even more so the fact that it demonstrated a common European understanding of these past deeds as monstrous crimes.